Recent developments in China are not only about clamping down on the internet sector. The government appears serious in its intent to promote greater fairness across the Chinese society. Many companies stand to see their earnings reduced by higher taxation, but also “voluntary” contributions to state-driven social projects. And perhaps durably so. Indeed, just like the current global inflationary pressures, we fear that the Chinese regulatory crackdown is here to stay.

Alibaba’s troubles date back to the final months of 2020. Policymakers began by scuttling the planned IPO of its Ant affiliate, soon after which they launched an antitrust investigation into the group, on grounds of anti-competitive practices. This resulted in a huge fine (12% of 2020 net earnings) being issued last April. Co-founder Jack Ma pretty much vanished from public view for several months, and Alibaba has shed roughly half of its value since its 2020 peak. But it was only when other technology names also fell under regulatory fire, notably online education providers, that broad Chinese equity indices began to tank.

Why such a clampdown by China’s authorities? Ultimately, it is probably all about protecting their one-party system. The Western world example of widening inequalities and internet juggernauts gaining huge fortunes, notoriety and political clout may well have played a part. The call from Beijing is ringing loud and clear: display of excessive wealth will not be tolerated, nor will gaining too large a following on social media. How seriously Chinese entrepreneurs take this threat is evidenced by the share of profits – in some cases over a billion dollars – that they have started to set aside for the financing of social projects promoted by the government. To the detriment of their shareholders, of course.

For Chinese company managers, all is not about making money. Social status (i.e. being respected) is just as, if not more, important. Which is why many are “voluntarily” participating in these social projects. And also why the stock prices of international luxury companies became under pressure lately. What point is there for Chinese customers to purchase luxury products if they cannot then wear or use them in public?

In our view, this is not just a transitory phenomenon that will impact only select companies/sectors and to which business models can readily adapt. Chinese authorities are determined to make their society fairer – and are backed in this respect by a good number of the country’s citizens. The consequences for the Chinese stock market – from all of this – are not so clear yet. The stock market remains an important source of (foreign) capital for Chinese companies and multinationals, and the government is fully aware of that. So why kill the golden goose? In the meantime, valuations do look attractive, particular on an international comparison, but future earnings are becoming extremely difficult to predict.

Anyhow: to be closely watched!

INFLATION NOW ALSO SURGING IN EUROPE

Inflation is another threat that is generally considered to be only temporary – meaning that monetary policy can remain ultraloose for the foreseeable future. And here too, we beg to disagree. We commented last month on the US consumer price index having passed the 5% mark. We note today that its Eurozone peer has hit 3%. Market pundits will retort that the core consumer price index stands at only 1.6%. But really, which is the version that people experience in their daily lives: with or without the food and energy components? We will leave it to our readers’ discretion.

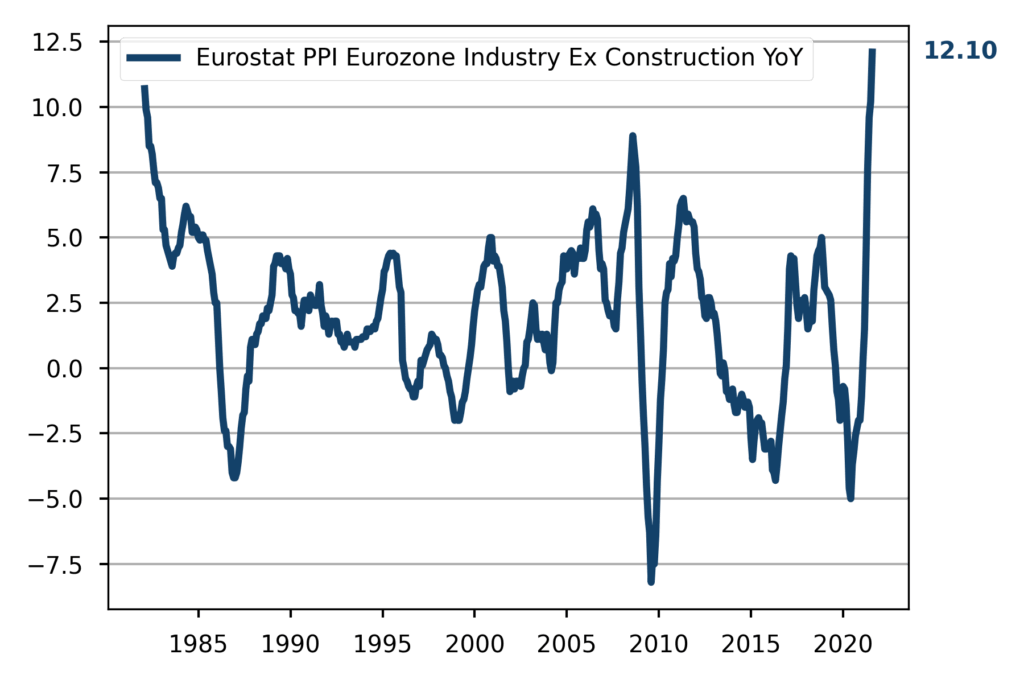

As for producer prices, they are progressing at an even more rapid pace, with the overall ex-construction index up 12% year-on-year and the manufacturing index up 8% – a high for both indices since 1982, when they were created.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that many entrepreneurs are drawing down on their inventories, to avoid transport costs that are swelling because of strong energy prices (see below) and multi-year high maritime freight rates as well as the post-Covid demand-supply imbalance.

Wages are clearly trending up too, despite still high unemployment levels, which suggests that some form of cost-push inflation may well be setting in.

OIL PRICES SET TO REMAIN STRONG

The gap between the all-items and core inflation indices is largely attributable to surging energy prices. Brent oil, the crude grade that is used in Europe, is now up 70% year-on-year, while gasoline prices have more than doubled.

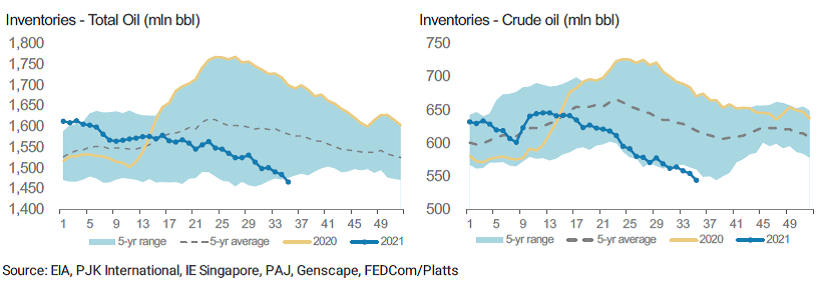

And this inflationary impact of energy looks set to continue. According to Morgan Stanley (see chart), crude oil inventories and total oil inventories (which include refined products) are now below the low end of their five-year range. The second half of the year being the seasonally high demand period, inventories will continue to be depleted even as OPEC goes ahead with its planned production increases.

In fact, the only reason the oil price is not above USD 85, given the current level of inventories, is because of concerns that OPEC could over-produce during the first half of 2022. Its stated plan is to increase supply by 400,000 barrels/day every month from today to September 2022 – at which point all capacity will have been returned to the market. Mapping the near-term path on the demand side is of course difficult, due to the spreading of the delta variant, but OPEC is closely monitoring market dynamics and could decide, at any point, to pause its production increases. There is no reason, in our view, to think that it will allow inventories to increase materially (beyond the normal first half seasonal build), particularly given the successful cohesion it has demonstrated thus far.

Looking further out on the horizon, when demand does finally return to normal the oil market will find itself in short supply. The US oil rig count is near the level it was at in 2016 when the WTI price dropped below USD 30, while the international rig count is close to its 2003 level. And the list of large projects about to go into production is looking sparse for the foreseeable future. Such restraint in capital spending stems not only from the 2018-2020 collapse in oil prices, but also – and somewhat paradoxically – from the pending “energy transition”. In effect, this is causing a hole in investments in new supply, in anticipation of a demand shift that has yet to happen.