Contrary to common assertions, we do not consider the situation on the energy front to be that rosy. Oil is once again trading around USD 90 per barrel, meaning that its past months’ moderating effect on overall inflation indices has disappeared, and even threatens to reverse going into 2024. European gas costs, meanwhile, appear to have bottomed out at levels still at least double what they were before the pandemic, with risks tilted to the upside if supply issues are not resolved.

Persistent inflation alongside a faltering (German) engine has effectively put Europe in a situation of stagflation – with some countries fully opening up the public subsidy purse and others unable to do so because of budgetary constraints. In turn, this makes for revived and worrisome tensions within the EU, but a potential earnings boon over the next years for a select number of companies.

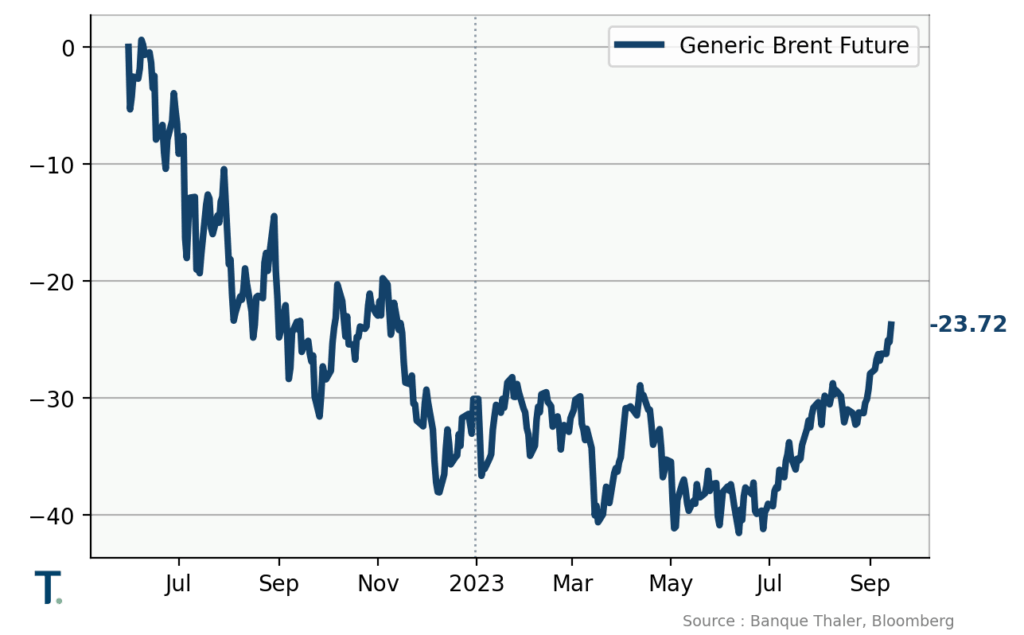

So far this year, oil has been a favourable factor for inflation, with lower year-on-year prices holding down CPI numbers. With the Brent now back up to USD 90, the level at which it was trading in the final months of 2022, these welcome base effects are about to disappear. Absent a drop in its price, oil will have a neutral impact on the inflation gauge during the next three months and then even contribute to push it up moving into 2024.

As far as gas prices are concerned, it is true that they have dropped by a factor of 10 since the (short-lived) spike of July-August 2022. But they are still double their pre-pandemic levels, which we consider normal given the changes in European supply sources. With very little gas still flowing through pipelines from Russia, the region relies essentially on LNG shipments from the US, the Middle East and North Africa, which is much more expensive. In fact, we fear upside risks to gas prices going forward, both in the short-term – if the coming winter does not prove as mild as the last one – and in the medium-term because of rapidly growing electricity demand.

Indeed, the ongoing drive for further and faster electrification (of transport and heating, amongst others) begs the question of how all the necessary power will be produced. Relying only on more solar plants and wind turbines is simply not a realistic proposition, as the Chinese example makes clear. With electrical car sales booming in China, authorities have invested massively into green energy production, yet not managed to meet the additional demand for electricity. Coal-fired plants are having to fill the gap, alongside large-scale nuclear projects.

In Germany, with the nuclear option off the table, the future promises to be even more complex. How paradoxical is it that German energy giant RWE recently had to resort to dismantling a wind farm in order to expand a coal mine?

Going forward, our take is that the various governments will (have to) focus more on gas-fired (rather than coal-fired) plants, making for growing global demand for gas and hence, as already mentioned, upward price pressure.

So, although CPI indices currently appear to be stabilising in the 4-5% range, the inflation problem cannot, in our view, be considered solved. And this is even before mentioning continued wage pressures, courtesy of still tight labour markets on both sides of the Atlantic.

Yet, bond markets seem not to take this sufficiently into account, with the yield curve still inverted across much of the maturity spectrum. Put differently, investors are still not getting a premium for longer maturities. So while we are progressively stepping up the average maturity of our bond portfolio (to between 2 and 5 years), we are for the time being avoiding the 6- to 10-year segment (the worst part of the curve in our view) and sticking to quality issuers.

For equity markets, a further rise in long-term interest rates mean downward pressure on valuations. Companies with potentially rising revenues and profits should thus be the focus for investors – and selectivity paramount.

Which brings us to governmental subsidies, a topic of much debate recently and that stands to strongly impact future earnings of certain industries and companies. European countries are feeling the pressure from the US Inflation Reduction Act, which was signed into law by President Biden just over a year ago and involves close to USD 800 billion of subsidies (in the arena of energy and climate change) for US-based companies. If the EU cannot soon find an appropriate response, there is a risk that European companies redirect their investment projects to the US. Swiss solar panel producer Meyer Burger is a case in point, having recently decided to open a solar cell factory in the US, at the expense of expansion plans for its Thalheim plant in Germany, lured by tax credits of up to USD 1.4 billion, a USD 300 million loan from the US Department of Energy, and a USD 90 million package from the City of Colorado Springs and the State of Colorado.

EU authorities, in reaction to the US “push”, now allow individual member states to support environmental and semiconductor projects on their territory. The problem, however, is that all European countries are not equal in their ability to grant such subsidies. Germany, clearly, can afford to do so. France is following suit, regardless of its rather shaky public finances – while at the same time working to get the temporary (Covid-related) exception granted with regards to the 3% maximum public deficit ratio (the so-called Maastricht norm) extended until the end of 2024. But the budgetary situation of other EU members such as Italy or Belgium makes it simply impossible for them to compete in attracting new industrial projects. Understandably, they would prefer that European industrial subsidies be funded and managed centrally. Just as they want to see the funds set aside by the EU for the energy transition start to flow through to the national level, rather than be held up by all sorts of administrative or regulatory constraints.

There is a risk that Europe be trounced by the US in the fields of energy transition and the “reshoring” of certain strategic industries. Which is not to say that European companies do not offer interesting investment opportunities. After all, from a stock market valuation perspective, it is the earnings outlook that matters, not where a company’s factories are located. Industrial companies operating in promising growth sectors such as recycling, insulation, glass, chip design and production, car manufacturing, etc. and that are able to play hard ball in obtaining government subsidies should not be missing from portfolios. They stand to be the winners of this decade and, strange but true, are also trading on relatively cheap valuation multiples…