Central bankers have painted themselves into a corner. After over a decade of ultra-loose monetary policy, justified first by the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 (to save the banks), then by the Covid-19 pandemic (to avoid an economic depression), they are on the eve of a new challenge: co-financing the planned and extremely expensive energy transition. In these circumstances, what option do they have but to keep interest rates very low such that ballooning public debts remain affordable? Can – and will – they take measures to curb the rapidly rising inflationary pressures? As the saying goes, it is a matter of choosing between the plague and cholera.

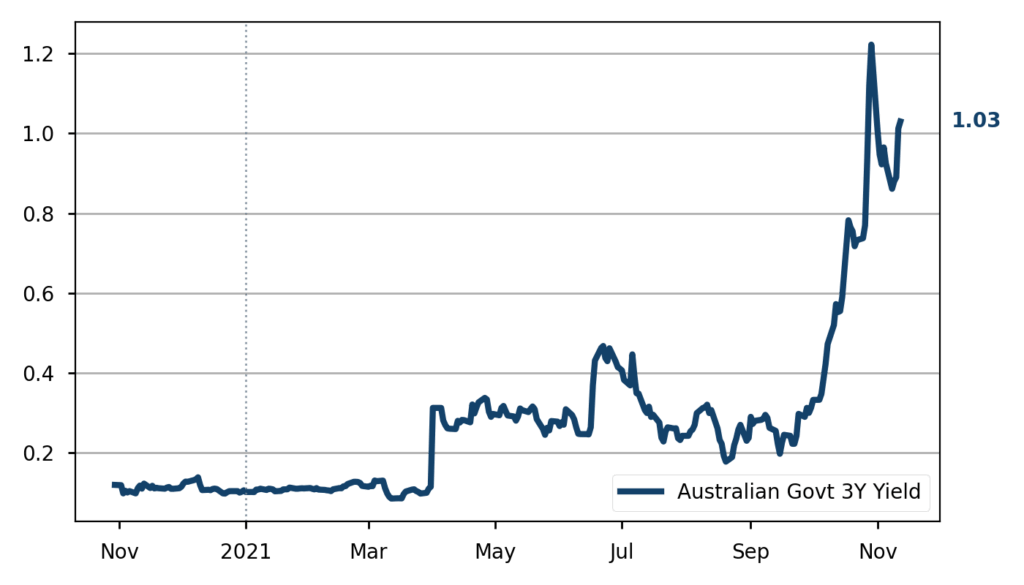

Recent developments in Australia are symptomatic of this quandary and suggest that the choice will not be entirely in central banks’ hands. Indeed, an October bond market rout saw three-year Australian yields rise by almost 1%, their fastest upmove since 1994, on investor concerns that inflation is spiralling out of control as the country finally emerges from lengthy and stringent Covid lockdowns. When the market-driven short-term yield got to 0.8%, eight times the central bank target, the Governor was forced to abandon the yield curve control programme – all the while trying to calm financial markets by saying that a central bank rate hike is not (yet) in the cards.

The Federal Reserve, while never having had the ambition to nail down the interest rate curve, is now facing the same dilemma. It just announced a tapering of asset purchases, meaning that it will very gradually reduce the printing of money going forward, but still envisages no rate hikes – sticking to its conviction that current high and rising inflation indicators are only transitory.

On this subject, the resurgence of Covid infections, especially in Europe, alongside recent measures taken by the Chinese government, urging citizens to stock up on daily necessities, is a matter of concern. The pandemic is clearly not over, with the current vaccines seemingly only partially fulfilling the promised protection.

From a consumer perspective, more home-working and perhaps partial lockdowns may again drive greater demand for internet-ordered goods. And from a producer perspective, a lack of workers due to illness would mean increasing difficulty to keep factories running. While this would help relieve the pressure currently faced by ports, with long queues of container ships awaiting unloading, such rising demand combined with constrained supply, at a time when inventories have already been depleted and some companies (e.g. in the car making and building industries) are struggling to get components, can generate only one outcome: further price increases.

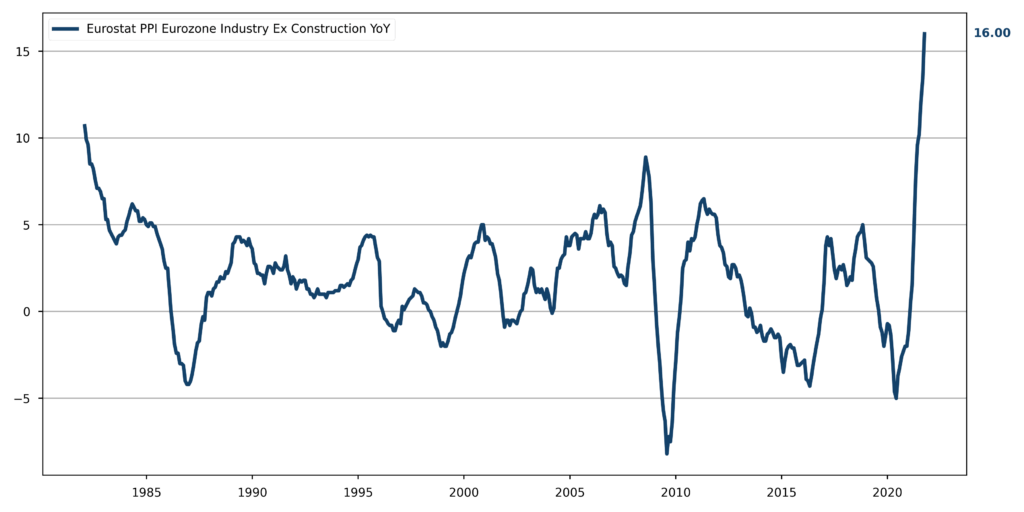

Inflation now tops 4% also in Europe and that is before probable price hikes on everyday supermarket items – that form a large portion of the CPI basket. For a pricing battle is currently raging between the big consumer products companies and the retail chains. The former want to push through price increases of the order of 5-10%, a move that the latter are resisting for competitive reasons. As part of this tug-of-war, some of the most-wanted products have started to go missing from supermarket shelves.

Add to that, growing wage pressures, US dollar appreciation and rising (traditional) energy prices, and it is difficult to share the major central banks’ complacent attitude. Whether they do allow inflation to remain durably elevated or eventually fight it by hiking rates, neither route bodes well for investors. Because of a loss of purchasing power in the former case, or a stock/bond market correction in the latter. This, unfortunately, is the very uncomfortable situation that we currently find ourselves in. The only way out is to (continue to) favour equity markets with a diversified approach and with special attention for shares of companies that have pricing power or are well positioned to benefit from the emerging wave of energy transition-related investments, while also holding some derivative portfolio protections.

Bonds, other than short-term, remain out of the question.

Reflections On The Energy Transition

As is being made even more prominent by the ongoing COP26 conference in Glasgow, huge investments will be required over the next decades to make the very necessary energy transition. Whether politicians will live up or not to their (generally more long- than short-term) promises, one thing seems sure: central banks will be called upon to provide unlimited funds at a low cost – just as they have historically always served to finance wars.

But, and this goes back to the corner that monetary policymakers have painted themselves into, the period during which these investments to “decarbonate” the world are made will involve even greater demand for traditional energy sources. Which, given their constrained supply, probably means not just higher oil prices (hence inflation) but also – and somewhat paradoxically – greater pollution for the foreseeable future. Take for instance the windmills that are widely considered to be an important part of the solution. They are made of steel to the tune of ca. 80%. And producing steel requires coal, a prime source of CO2 emissions…

And then there is the question of nuclear power. Massive deployment of wind- and sun-driven power stations is certainly paramount, but the fact remains that they do not produce constant quantities of energy. Worse, some 15-20% of the time neither is very productive (i.e. they cannot offset each other). It is thus “common sense” to us that nuclear power be coming back onto certain countries’ agenda.

Common sense but also, and that will be our final point, geopolitical considerations. From a European perspective, betting only on windmills and solar panels effectively means increasing dependence to Chinese factories. And renouncing nuclear power (France being a notable exception in this respect) means increasing dependence to Russian gas. Activism is important but so is a certain dose of pragmatism…