Equity markets were in good spirits during the final weeks of 2023, buoyed by receding inflation expectations – hence hopes for rapid rate cuts. Increased geopolitical concerns were blithely ignored in the process. But what are the odds of the Federal Reserve pivoting monetary policy as drastically as anticipated in 2024? And how likely is a ceasefire in Gaza and Ukraine?

The latest forecasts from Federal Reserve members (“dot plot”) points to a short-term interest rate around 4.75%. This thus suggests that US policy rates will be cut three times (by 25 bp each) over the next 12 months, versus the six cuts currently priced in by financial markets. Where the needle actually settles will of course depend primarily on future inflation data.

In this regard, we note on the one hand that December saw price indices move back up in France and Germany – partly due to the oil price-related base effects that we described in prior editions of this letter. On the other hand, the pickup is proving more limited than anticipated, the current oil price being much lower than most analysts (us included) would have expected.

While oil demand was somewhat higher than forecast in 2023, thanks to the global economy not plunging into recession, it is mainly from the supply side that the surprise has stemmed. And not within OPEC, which stuck to strict production quotas during 2023, nor indeed Russia, where output just managed to remain stable, offsetting European sanctions by sales – at a capped price – to China and India. No, the surprise came from US production, with unlisted shale companies again drilling and pumping as if there was no tomorrow. The US has thus now become the world’s largest oil producer, with output exceeding 13 million barrels per day. Not a scenario that one would have readily foreseen under a supposedly environmentally-conscious Biden administration.

With prime acreage now largely exploited, US shale production is likely to level off in 2024, and then fall back somewhat from 2025 onwards. Still, for the coming months and absent a serious turn in the Middle East conflict, we would argue that the oil price is capped. Which, coupled with the intense pressure to cut rates that central banks are coming under from (heavily indebted) governments, suggests that financial markets are indeed correct in anticipating that monetary policy will soon be pivoted. That said, because core inflation (excluding food and energy) remains high and the labour market tight, we expect the magnitude of the rate cuts to be closer to what central bankers are currently suggesting, than to what investors are speculating on.

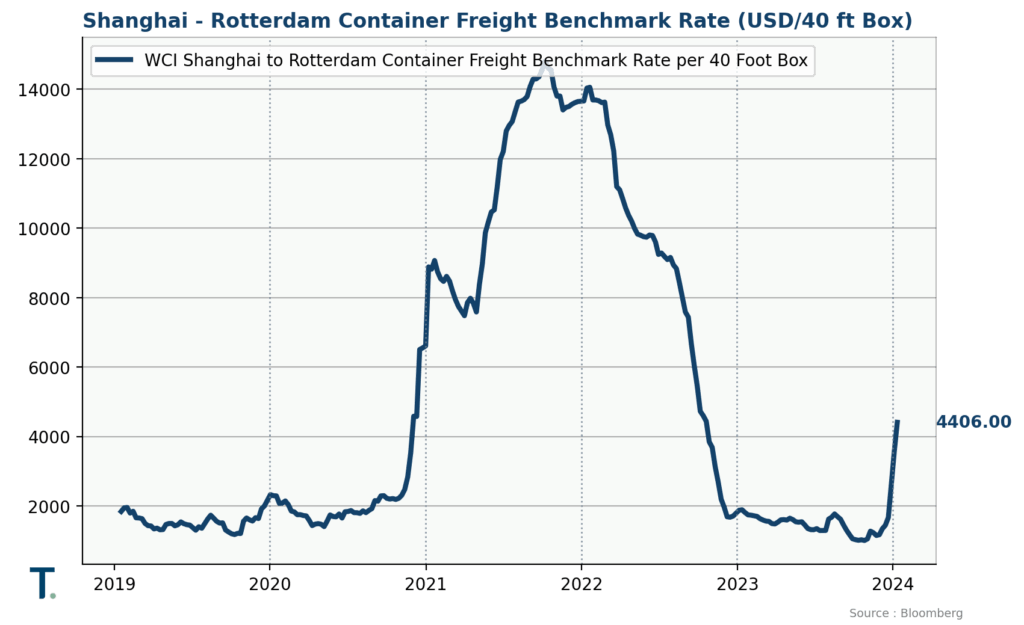

Turning to the geopolitical situation, attacks on cargo ships in the Red Sea (by Yemeni Houthi rebels) have been all over the news lately, with not always pertinent conclusions in our view. Freight rates from Asia to Europe have clearly risen, either because ships have to take the longer route around Africa or because they run up additional security expenses and higher insurance premiums if they do sail through the Red Sea and Suez Canal. But the extent of the cost increase is nowhere near what was experienced during the pandemic – in part thanks to a more plentiful fleet capacity at present.

Also, the two-week delay due to re-routing is more manageable today for Western companies that it was a couple of years ago, most of them having redesigned their inventory management systems and “just-in-time” production processes after the Covid troubles. They now hold “strategic” stocks so as to be able to cope with unforeseen supply chain issues. And, of course, the delay in merchandise delivery because of the longer route needs only be dealt with once: subsequent shipments will then arrive according to their usual periodicity.

As such, we would argue that a partial blockade of the Red Sea – and, derivatively, the Suez Canal – is manageable. A closure of the Strait of Hormuz, however, would be a very different story. For that would mean that Iran has decided to “formally” participate in the Middle East conflict, as opposed to its current proxy approach of supporting Hezbollah forces in Lebanon and Houthi rebels in Yemen. Gauging the risk of such an escalation of the war is of course near impossible, but it does in our view argue for remaining cautious. Indeed, it seems unlikely that equity markets would be able to continue to ignore geopolitical risks in such a scenario.

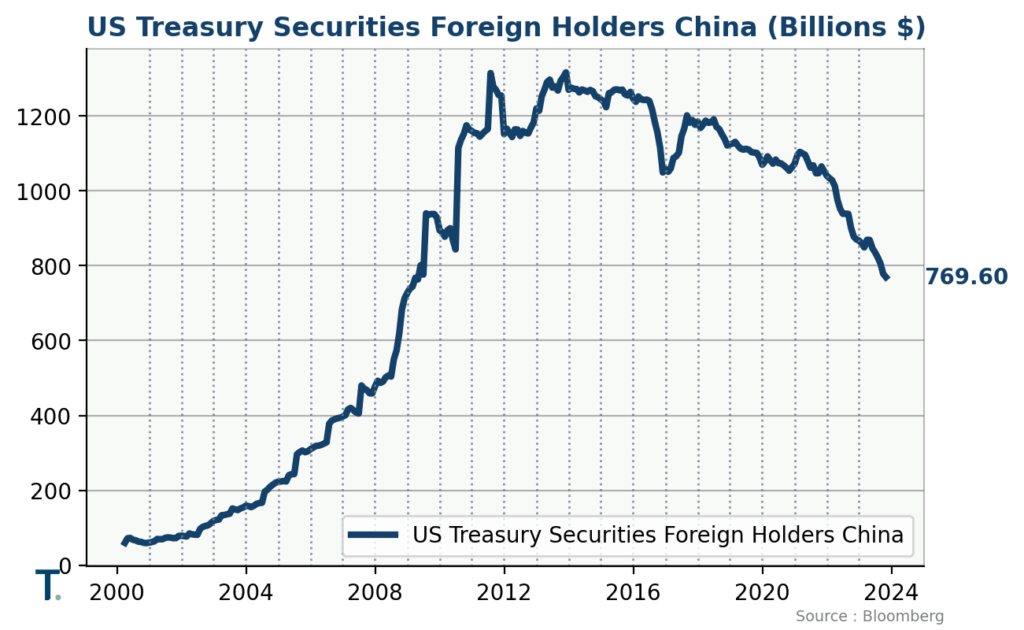

With bond markets having seemingly also anticipated upcoming central bank rate cuts, we are advocating slightly shorter maturities (ca. 5 years), expecting market rates to back up a little over the coming weeks after their perhaps overly enthusiastic decline of the past few weeks. Amongst other things, this also has to do with the US Treasury’s need to find buyers for its new bond issues to cover significant budget deficits, and to replace sellers of US government paper (China et al).

Sellers of US government bonds seem to be (partially) reinvesting/diversifying into gold (and perhaps the Swiss franc?), judging by the recent strength in the bullion (and the Swiss franc). Having experienced how the US have used the power of the dollar as an international trading currency to exert political pressure in recent years, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) may well have opted to replace its stock of US Treasuries by, amongst others, gold reserves as a first step towards promoting a new (gold-backed?) reserve currency. Incidentally, the PBoC is not the only central bank to be currently stockpiling gold…

In a nutshell, the geopolitical situation remains very volatile and that is unlikely to change in 2024. Sooner or later, this will have to be offset by a risk premium – which will translate into lower (equity and bond) prices. As such, our message is to remain cautious and well diversified. Tactically, a slight reduction in the average maturity of the bond component of portfolios is also not a bad idea in our view.

It remains for us to wish everyone a happy and peaceful 2024, with hopefully stable financial markets.